There were several good, ambitious exhibitions in Seattle this summer, timed to coincide with the second annual Art Fair. To get a sense of what is going on in the Pacific Northwest and learn about those ambitious undertakings follow these links: Art Fair and Out of Sight v.2 at the King Street Station and Seattle’s Center on Contemporary Art COCA – now relocated to their new space. UW’s Henry Gallery, presented Senga Nengudi: Improvisational Gestures, a captivating exhibition featuring her sculpture, installation, and videos that were exciting to see in the Pacific NW.

Rembrandt, installation view Graphic Masters, Seattle Art Museum

Last June I referred to the now closed exhibition of Graphic Masters at Seattle Art Museum and other printmaking shows that I saw this year, Munch and the Sea at the Tacoma Art Museum, and Van Dyck, Rembrandt, and the Portrait Print at the Art Institute of Chicago. It is always exciting to see exhibitions that feature prints and works on paper, especially at institutions that have first-rate collections with rare and often multiple impressions of an image. Having viewed many of these art works in various exhibitions over several years, I still find it refreshing and stimulating to see these beautiful art works. Seeing some of these old favorites from over the centuries is like visiting friends, friends with whom it feels like no time has passed in between visits, and it demonstrates how relationships grow deeper through repeated visits. I was reminded of the first time I saw a major exhibition of Picasso prints at LACMA. It was an exhibition of over 400 artworks, just two years before his prolific output of 1968.

For the Graphic Masters exhibition, the introductory gallery featured a small selection of Rembrandt etchings, some from his hand, and a few from others who worked for him in a more reproductive manner. These prints demonstrate the beauty, power, and expressive potential of hand-printed images by the artist. Rembrandt was a master who wasn’t merely content to use the medium and process as mechanical reproduction or for distribution/dissemination; as always, he challenged conventions and expectations. I was left with a desire to see a few more even though it was evident there was going to be a lot to look at as we entered the other galleries. Still though, I wish there had been more of these beauties.

Durer, installation view Graphic Masters, Seattle Art Museum

Seeing first-rate impressions of Durer woodcuts and engravings is always amazing; they are staggering in their beauty and execution and it’s a joy to see any example of his artwork. Having an opportunity to stand in front of these works, to study their detail and let one’s mind wander, is, simply put, one of life’s pleasures. The narrative doesn’t always speak to me personally, but some do and are regarded as among the classics. In the next gallery, Hogarth’s two well-known series of engravings were presented: The Harlot’s Progress, 1731, and The Rake’s Progress, 1735. The acceptance and popularity of these two series of images led to unauthorized reproductions, which resulted in Hogarth successfully lobbying Parliament to enact the Engraver’s Copyright Act, regarded as the first copyright law.

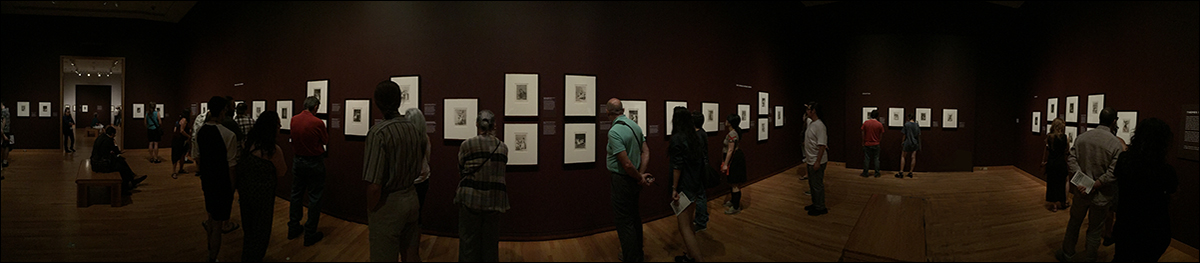

Goya: installation view Graphic Masters, Seattle Art Museum

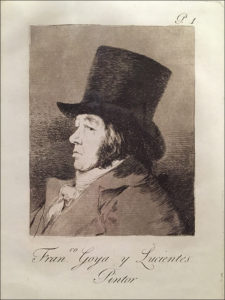

Self-portrait, Etching and Aquatint

The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters, Etching & Aquatint

Goya’s Caprichos fill the next galleries. One of the classic series in the history of art, these 80 images have held up well over the centuries, and have grown to iconic status since they were first published in 1799. I’m including a link to Los Caprichos on Wikipedia as the images are included and thoughtfully presented. The previous galleries were well attended and full, but the Goya gallery was packed, requiring patience to have a turn to view the images. They are classics; the enthusiasm and reverence of the visitors fully attests to the power these images can exert on viewers. The audience was captivated by Goya’s depictions of folly that continue to demonstrate how some things never change. What he created then is as relevant today in the 21st century as when they were published in 1799. Having had many opportunities to see examples of these images from the different editions, in other exhibitions and museum study centers, it is always challenging to consider the differences in subtle detail, dependent on which edition they are from. The later editions are still worthy of study, admiration, and collecting, even though some of the subtle, delicate passages have been reduced due to wear of the copper plates. So when we have a chance to see examples from the first edition or an impression before letters it is a rare treat.

Another aspect, unique to printmaking, and an area of personal interest to me is the state proof, or changes in an image that are recorded by printing to see how the image is evolving, thus providing the artist with a real-time example of what the image looks like at a given state of it’s development. Rembrandt is perhaps recognized as the earliest artist to make use of this aesthetically, fully realizing the expressive potential in similar yet different aspects of images. He reveled in manipulating the ink film, from light and misty, to dark and foreboding, haunting, mysterious, and beautiful.

Picasso, installation view Graphic Masters, Seattle Art Museum

Satyr and Sleeping Woman, 1936, Aquatint

Picasso too was aware of the expressive potential in exploiting the medium he used. There are well known examples of how he used a medium to powerful effect, and would challenge his printers to do something that wasn’t expected to yield positive results. On occasion we can find examples of a state proof that has become a totally new picture with subtle evidence remaining from a previous version. Always curious, he wasn’t content to simply use any given medium without pushing against its boundaries to break into new territory.

Blind Minotaur Led by Girl with Bouquet of Wild Flowers, 1934, Drypoint with scraping and engraving

Minotaur Kneeling Over Sleeping Girl, 1933, Drypoint

Often when you’ve seen many exhibitions of an artist’s work, familiarity leads to the expectation that you’re likely to see a number of prints from other exhibitions, things we’ve seen before, and yes, they were in this exhibition too. But seeing them afresh and in this context was like seeing them anew. Perhaps it’s just that the more one sees the images, the more one sees in the images. A deeper understanding and appreciation is gained seeing them in new and different groupings. His art reflects all aspects of his life and times, his loves, joys, turmoil, and conflicts on the international stage. He masterfully used timeless, classic themes and symbols to address the topics of his day – just as Goya and other artists had before him. It is interesting to note how context and titles can change how different audiences approach the work. A scholar, curator, or translator may interpret a title literally, or see the meaning change from the title’s original language. Much has been written about the artist, his art works, and his personal life. Sometimes interpreting themes on too much of a personal level can deter one from exploring the more complex and historically-specific meanings of a theme like The Rape of Europa, where one should also consider the symbolism of the mythological beast that represents tyranny and oppression of peoples and nations ravaged by war.

The final section of the exhibition is devoted to the drawings of R. Crumb, The Bible Illuminated: R. Crumb’s Book of Genesis. Taken as a whole, this is an impressive body of work, drawings executed in black and white, pen and ink in his distinctive style. The drawings resulted in the WW Norton & Company 2009 publication of the graphic novel of the same name.

The Bible Illuminated: R. Crumb’s Book of Genesis Seattle Art Museum

This set of original drawings differs from other works in the exhibition in that they serve the function of drawings that were used in the production of the publication. And of course, they are drawings while all the other works in the exhibition are in various print media: woodcut, engraving, drypoint, etching, aquatint.

This was an exciting exhibition covering a wide ranging approach to the graphic arts, which provided the opportunity to see a few of my all time favorite images again. However, I was left with a question: were male artists the only significant contributors in this field? Käthe Kollwitz comes to mind and would have been an interesting bridge between Goya and Picasso; Mary Cassat, Louise Bourgeois, Helen Frankenthaler, or among contemporary artists, Jaune Quick to See Smith and Malanie Yazzie have a long standing practice and highly regarded bodies of work in the field of original graphic arts, as does Vija Celmins with her drawings, etchings and mezzotints.

Taken with the other museum exhibitions devoted to printmaking that I saw this year (at Art Institute of Chicago and Tacoma Art Museum), it was refreshing to see such high quality images, including some rare impressions, and it was also encouraging to see the response by the visitors. It seemed as if the public was very enthusiastic about looking at these images, both overall, as in the big picture, and close-up, studying the detail with the museum-provided magnifying glasses in the galleries.

Elsewhere in the museum, it is always a pleasure to seek out different aspects of the collections and see what the curators have selected for display. Indeed it was exciting to see some recent additions to the collection, and in particular, several works from Virginia Wright and her family, who have been generous supporters of the arts. Some of these art works were last displayed in 2013-14 at the Wright Exhibition Space before it closed, and which I wrote about here. As with my fascination with state proofs in printmaking, or contact sheets in photography, I find it very interesting to see art works and exhibitions displayed in different venues – how works are situated in a space, their relationship to other works, context, and effect of how lighting can change the feeling of specific art works. Some of these works will be on view in the Light and Space exhibit at SAM until November 6, 2016. If you are able to visit the museum during this time period, look in adjacent galleries, for a video of John Cage on the television program, I’ve Got a Secret, and two paintings from the collection by Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock (images included in the slide show below).

- Graphic Masters Seattle Art Museum

- Rembrandt, installation view Graphic Masters, Seattle Art Museum

- Durer, installation view Graphic Masters, Seattle Art Museum

- Self-portrait, Etching and Aquatint

- Goya: installation view Graphic Masters, Seattle Art Museum

- The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters, Etching & Aquatint

- Picasso, installation view Graphic Masters, Seattle Art Museum

- Minotaur Kneeling Over Sleeping Girl, 1933, Drypoint

- Satyr and Sleeping Woman, 1936, Aquatint

- Blind Minotaur Led by Girl with Bouquet of Wild Flowers, 1934, Drypoint with scraping and engraving

- Picasso, installation view Graphic Masters, Seattle Art Museum

- The Bible Illuminated: R. Crumb’s Book of Genesis Seattle Art Museum

- Jackson Pollock, collection Seattle Art Museum

- Mark Rothko, collection Seattle Art Museum